American Psycho (Movie Review)

The 2000 film American Psycho was adapted from the Bret Easton Ellis novel of the same name and brought to the screen by director Mary Harron. With an impressive amount of hardcore gusto within the film's reels, Harron manages to deliver an experience that feels completely separated from its novel predecessor without conjuring anger from too much of a derailment. While this is the film's greatest asset, it also quickly becomes problematic after the first few scenes. A story about a yuppie businessman that dreams of killing his equally pious friends and colleagues is an intriguing one, but the contents of that tale desires a certain level of accessibility. The anti-hero is a compelling figure, but in American Psycho the concept of anti-hero is eradicated once the idea of sympathy for the yuppie is completely null and void.

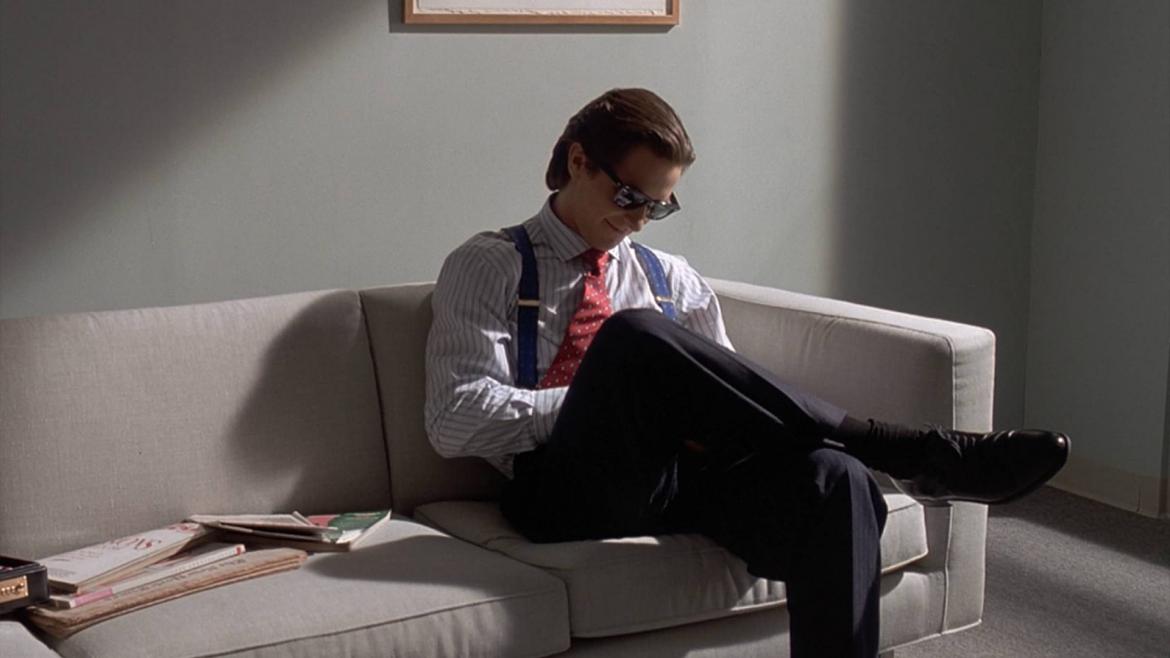

Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) is the perfect specimen of the American dream. Young, handsome, and dedicated to his craft as a businessman, Bateman spends a majority of his time finding various ways to stand out past his already God-like persona. Chemical peels, new business cards, and sleeping with any woman he can get his hands on are just aspects to his daily routine. The only lingering issue in Bateman’s psyche is one that is quelled by blood, especially the spillage of those that undermine his persona. Using his muse of “Huey Lewis & The News” to get the killings started, Bateman begins to pick off every co-worker that inspires even an ounce of jealousy, as well as any woman that doesn’t satisfy him in the bedroom.

It’s undeniable that American Psycho lives up to its name on the page and on the screen. A portrait of a serial killer that lives the high-life, Bateman’s character is one that’s difficult to get behind. Characters like Dexter Morgan follow a similar suit, but the inclusion of a “code” and overall comedic internal monologue allows the viewer to connect on even the smallest empathetic level with the killer. Bateman’s unwavering arrogance and attraction to all things despicable creates a segregated viewing experience. Either his internal struggles with wanting to kill his yuppie co-worker over jealousy of business card font will leave the viewer cackling, or settle in the notion that this man is an unhinged representation of killers such as Ted Bundy. However, it’s imperative to note that Bateman’s lack of relatability does not make this film a tragedy, in fact, that aspect is exactly why American Psycho stands out against other studies of America’s killers. The film does rely on dark humor, as it should, and that ultimately gives an experience that a majority of audiences will appreciate.

Where the film starts to lose its foothold is in the sex scenes. The balance between comedy and horror works extremely well as Bateman expresses his knowledge of “Huey Lewis & The News” to his potential victim, but that beautiful dynamic is lacking in the intimate scenes. The sequences are essentially shot as cinematic porn, which is an apt choice to make as Bateman would have that type of sexual lifestyle, but the winking, sadistic humor is lacking and is instead replaced with sheer horror as Bateman dominates his sexual victim that leads into a physical victim. The balance could have been brought into these scenes to drive home Bateman’s split personality, however the “hardcore” approach seemed to be the favorable choice in the creators’ minds.

Overall, American Psycho is a film that is an accomplishment in adaptation. Delivering such a deplorable character to the screen with an immense amount of witty dark humor is not an easy feat, and Harron proves that honoring source material to the fullest extent pays off beautifully.