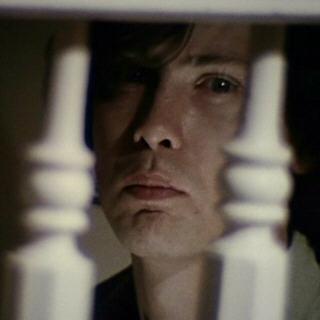

Martin (Movie Review)

George Romero’s earliest pictures strike that wonderful balance of achieving both crowd-pleasing cult sensations as well as academic and journalistic esteem. While Romero may be inseparable from popular zombie-dom* it is his 1976 “vampire” film “Martin” that represents one of his most surprisingly sincere, character driven films, making use of horror conventions as a frame for a truly unique take on the relationship between the monstrous, horrific, and social world.

The film’s narrative follows the titular character’s experiences with his older cousin, Tada Cuda, who attempts to redeem Martin’s soul before finally killing him. Both Cuda and Martin believe him to suffer from the “family curse” of vampirism. Up to this point we have little reason to doubt this belief. The film opens with a prolonged sequence in which Martin kills a woman in order to drink her blood. However, not all of the old myths seem to be holding water. Upon entering Cuda’s home, Martin is subjected to all manner of tests. Wreaths of garlic are hung from bedroom doors and crucifixes are thrust in Martin’s face. Each attempt fizzles. “There isn’t any magic!” Martin screams as he bites into a bulb of garlic. And then there are the real questions: Why does Martin not have protruding canines, why does he eat, and why can he walk around in the daytime unaffected by the sun? The remainder of the film follows Martin as he encounters other residents of Pittsburgh including Cuda’s granddaughter Christina and a lonely housewife with whom he carries on a sexual relationship. The cinematography employs a “slice-of-life” style with loosely framed, handheld shots. The ultimate goal here doesn’t seem so much to answer the vampire question as it is to depict Martin’s predicament in relation to the world around him.

"Martin" draws contradictions between a number of more traditional narrative elements familiar to horror (and U.S. cinema in general) including familial/romantic relationships, economic disparity, and religious folklore. Christina and her long-term boyfriend (Tom Savini, oh yes) are constantly bickering. The young, wine swilling, cigarette-smoking priest at the church they attend finds Cuda’s belief in exorcism and demons quaint if not slightly laughable. Our only other glimpses of organized religion are low angle shots of imposing steeples that are utilized as visual bookends to a number of violent moments. Pittsburgh is shown to us as a derelict ruin with pockets of wealthy, unhappily married heterosexual couples.

Throughout the film Romero cuts to shots of abandoned factories, dirty, empty alleys, a homeless man living in a train platform bathroom, dogs scavenging through trash, and a junkyard where wrecked automobiles are compacted to small cubes. This last setting proves a potent visual motif given Pittsburgh’s long history of steel production. The cycle of impulsive consumption and destruction is made quite apparent. This is a world in which all traditional institutions are slowly decaying and feeding on the individuals so invested in their reliability. The fact that Martin’s vampirism — whether actual or psychological — comes from his family is also indicative of this theme. The editing style employed connects these moments together like one long patchwork of experience. Rather than causally connecting scenes through consistent time and place, Romero builds these themes out of the fragments of everyday life. Cuda may call Martin “nosferatu” and “vampyr” but the name could easily be applied to everything surrounding them.

What is at the heart of these visual and narrative juxtapositions is the dynamic between the idealized and actual reality of Martin’s world. This tension is a major pivot point upon which Romero really gets to the meat of the film. This becomes more evident when considering the fact that the supposed monster, Martin, is our narrative focus and point of identification. Rather than depicting him as that monstrous other seen by another character, Romero structures the film from his perspective. Martin is not that outside evil. He is part and parcel of the failures of traditional institutions. The film’s representation of violence is indicative of this theme. Martin’s attacks are presented as methodical, precise, and purposeful if not just a touch sloppy at times. Conversely, the violence committed by Cuda, police officers, and drug-dealing gangsters is presented in brutal montages. Close-ups of skulls erupt into sprays of blood while bodies are pierced or crushed. This isn’t to say that one is less violent or horrific than the other. Rather, Romero is drawing a correlation between violence that is enacted passively through the coercion of the social world and violence that comes from that world outright. This point is further accentuated by the fact nearly all of Martin’s attacks are cross-cut with black and white footage of Martin in an idealized rendition of future and current events set in a Victorian mansion. His fantasies are the empty promises of social vampirism.

But what is fascinating about Romero’s use of the vampire myth in "Martin" is that vampirism is not only used as a foil for real world problems, but that the characters within in the film also project vampirism as a scapegoat for simplifying and destroying complex social realities. The film comes to us at an interesting point in U.S. cinema history as the New Hollywood sputters to a close, production studios are subsumed into huge conglomerations, and the blockbuster becomes the “it” formula. On the political level, the United States was witnessing widespread economic decline and the failure of more progressive political ideologies. We see equal parts artistic innovation, social malaise, apathy, and also some of Romero’s earliest efforts to invert metaphor in horror. The prolific film theorist Robin Wood has said that the essence of horror is the monster’s threat to normality. "Martin" takes this theme and creates a monster out of the everyday normal. "Martin’s" vampire is the insistence of maintaining conventional social hungers and the impossibility of their fulfillment.