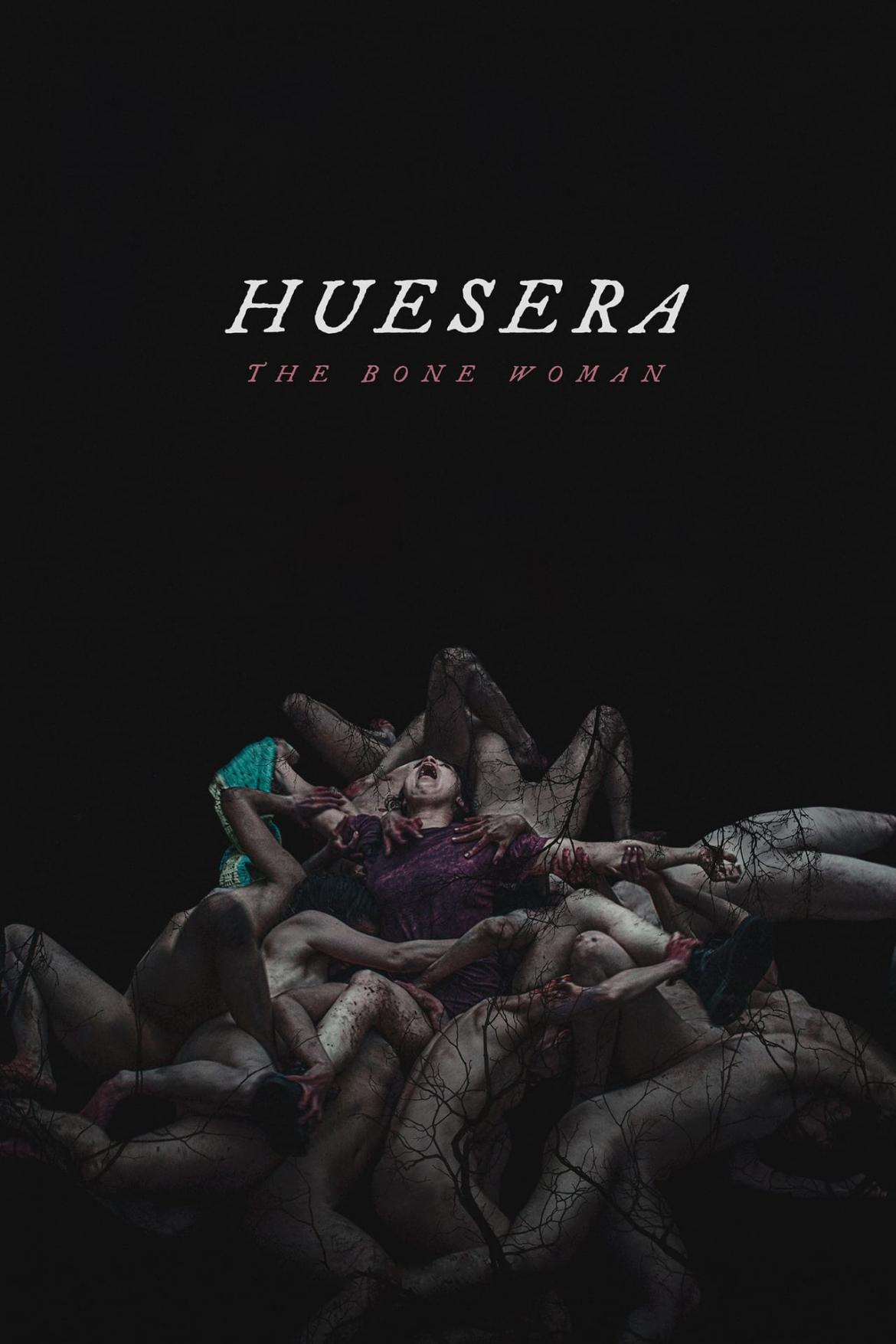

Huesera: The Bone Woman (Movie Review)

I hate the term “elevated horror.”

The movies that it’s often associated with — It Follows, The Witch, Hereditary, etc. — are excellent. Many of these films have an arthouse feel, where characters are morally gray, dread and mood take precedence over scares or gore, and the “meanings” of the films can be ambiguous and manifold. Is It Follows a parable about the danger of sexually transmitted diseases? Is The Witch positing that the protagonist can find liberation from the pressures of society in witchcraft? I don’t know. Ask a smarter film critic those questions. (Or better yet, visit us on Facebook or Twitter @bghorror to wax philosophic about these films).

However, “elevated horror,” the term coined to describe this wave of moody, thoughtful films, has been mostly destructive to the conversation in the horror community. “Elevated” is so loaded — how else can we read it except to mean “inherently better?” — that we can’t talk about it without devolving into polarized camps of adulation or rejection. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: “I only watch elevated horror. It’s deeper. It has more complex themes. Besides, it’s not like horror movies have to be scary.” Or this one: “What’s with this pretentious bullshit? People just like to pretend to be smart when they watch these. Just give me a new Friday the 13th that doesn’t suck.” (If you haven’t heard anything like this, congratulations, you probably spend a healthy amount of time online. As the saying goes, touching grass once a day keeps the brainworms away.)

Put simply, the arguments around “elevated horror” always devolve into the age old contention betweens “slobs” and “snobs,” and we are all the dumber for it. Bless the writers of Scream 5 (5cream, if you’re nasty) for taking a — ha ha — stab at satirizing the debate, because this is a term we need to laugh at and put to bed. “Elevated horror” will pass. I remember when the horror community was arguing about “torture porn” and “J-horror.” If you’re too young to remember those terms, go pick up a copy of Rue Morgue or Fangoria from the 2000s. Instead of complaining about horror devolving into pretentious bullshit, people were arguing about horror devolving into crass, exploitative violence or watered-down jump scare bullshit. Some things never change.

I feel like have to serve a buffer against criticism that Huesera: The Bone Woman is another one of these “elevated horror” films, because I’m afraid some of you are going to dismiss it without giving it a chance. To preface, yes, it is another moody drama-cum-horror film with morally gray characters and an ambiguous resolution, but I’m hoping you will give it a chance. Huesera is the story of a pregnant bisexual woman slowly wrenched apart as she tries to fulfill the desires of society, family, an old flame, and her self, all while an evil presence lurks in the background of her life. The story operates on folk tale logic, where Valeria’s curse is unjust, implacable, and comes from nowhere. And does Valeria survive at the end of the film? Yes and no.

[light spoilers follow]

In order to really talk about Huesera, I will have to get into some spoilers, because there is a such a dearth of explanation in parts that it requires analyzing the film through the lens of symbol or metaphor. Director Michelle Cervera has created one of those films that begs discussion as soon as you leave the theater.

Valeria (Natalia Solián) and her husband Raúl (Alfonso Dosal) are trying to have a child, and the film starts with a prayer, conception, and a positive pregnancy test. The couple’s joy is infectious and believable, but little moments of tension chip away at Valeria’s excitement. She is a carpenter. It’s her trade and her mode of self-expression. She starts the film by building a crib for her yet unborn child with the dedication of earnest love. However, her doctor admonishes her not work with the power tools. Her work room is being converted into the baby’s room. Her mother-in-law, Norma (Anahí Allué), buys a crib with full knowledge that Valeria is already building one. No and no and no follows her.

As if the closing avenues of self-expression aren’t enough, Raúl won’t even sleep with her when she’s pregnant, afraid that sex will harm the baby. And before you ask, no, it’s a myth that you can hurt the baby by having intercourse while pregnant. It’s not my job to teach sex ed during movie reviews, but I’ll be damned if I let that bit of misinformation slip by.

Enter la Huesera, an unsettling figure that crawls on all fours, her broken legs grinding as she scurries across the screen. Is she the woman from Mexican folklore? Is she solely a creature of Valeria’s imagination? The film doesn’t clear up the ambiguity, but it does establish a line of demarcation. Her husband and her family lie on one side, where the bone woman is not real and Valeria is losing her mind. On the other side are her aunt Isabel (Mercedes Hernández), folk diviner and healer, Ursula (Martha Claudia Moreno), and her aunt’s friends, who represent a kind of spinster sisterhood that embrace the supernatural and respect Valeria’s plight.

Enter also Octavia (Mayra Batalla), Valeria’s ex-girlfriend and a connection to our protagonist’s past. We learn that Valeria used to be a punk, hanging out late drinking with friends. However, she broke it off with Octavia, choosing to make her parents proud by staying where she grew up and going to college. Again, the film denies a simple explanation. Did Valeria grow out of the punk lifestyle and choose Raúl, or did she conform to societal expectations? Can it possibly be both, and is she crumpling under society’s pressures nonetheless? And is it too late for Valeria to choose a different path?

In some ways, I found these ambiguities frustrating, because I was waiting for a final aha moment where all was made clear. In fact, Huesera does the opposite, because it has the perfect folk tale ending: the Valeria of the beginning may not be the same one of the story’s end. Even the question of whether Valeria is la Huesera — her mother-in-law so helpfully tells her that childbirth will feel like bones breaking — is up for debate; you will have to watch the film to find out. Yet, these very questions add rich layers to the story. The ambiguity is part of the charm.

I predict that Huesera: The Bone Woman will divide audiences, but the advantage of a film that traffics in the symbolic is that it is rich in imagery. The film ends in a harrowing climax, where Valeria undergoes a final ritual that will haunt audiences dreams. The audience may come away divided, but maybe they will come away changed like Valeria after seeing this film. Maybe the audience too will learn what it means to be subsumed.