Welcome to the Comic Century

Unless you've been napping for the last couple of years, you've probably noticed that superheros have become a mainstay at the theater. This weekend, "The Incredible Hulk" becomes the second of Marvel Entertainment's properties to hit screens in 2008, and other comic properties will follow soon thereafter. The flow of comic book adaptations hasn't always been this strong though, and in fact, toward the end of the 20th century, one wouldn't have been out of line for thinking we'd never see some of comic's biggest names put to film. The turn of the century, however, brought with it a new group of filmmakers with the vision and ability to bring the panels of popular comic books to life.

The granddaddy of them all, Superman, made his big screen debut in 1978. Audiences flocked to the theaters to see Kal-El reverse the Earth’s rotation and avert tragedy. With worldwide box office receipts topping $300 million, the film made a star of Christopher Reeve and spawned three sequels over the next nine years, each of which saw diminishing returns.

In retrospect, The Man of Steel opened the floodgates of Hollywood, unleashing a swell of superhero and comic book related films. While there were only two widely released films drawn from comic books in the 70’s, that number grew to nine by the 80’s, and swelled to 28 in the 90’s. All told, there were 39 widely-distributed films based on intellectual property that originated in comics or graphic novels between 1978 and 1999. Put more simply, filmmakers had found a new source of inspiration, and film goers were more than happy to indulge in this new outlet for cinematic escapism.

It was in the middle of blockbuster season 2000 that director Bryan Singer brought “X-Men” to the movie going masses. The previous year, superhero films had seemingly grown stale—1999 saw the release of the parody film “Mystery Men”—but “X-Men” signaled the beginning of a new cycle of comic book inspired films. With better technology making high-end CGI and special effects less of a budget drain, directors like Singer were able to create more realistic superhero films. While Marvel’s premiere team set a template for success (grossing nearly $300 million worldwide on a budget of $75 million), it would take two more years before Sam Raimi would set loose his imagination on one of Marvel’s flagship properties, announcing loud and clear the arrival of a new golden age of comic book inspired films—The Comic Century.

The year that Spider Man broke every box office record at the time with a $114 million opening weekend, there were three other comic adaptations to hit the big screen, but while each fell within the timeline of the Comic Century, none of those films (“Blade II,” “Men in Black II,” and “Road to Perdition”) operated as cleanly within the frame work of what Singer and Raimi, via Fox and Sony respectively, had done. The ground work had been laid though, and each successive year saw studios rushing to put out more and more comic book inspired fare. In 2003 there were five; in 2004, six; and by 2007, audiences were treated to seven comic films. This year, the ninth of the Comic Century, we will see another seven films: “Iron Man,” this week’s “The Incredible Hulk,” “Wanted,” “Hellboy II,” “The Dark Knight,” “Punisher: War Zone,” and “The Spirit.”

All told, since “X-Men”’s debut, there will have been 40 widely released comic adaptations come the end of 2008. That’s an average of more than four a year. Whereas in the ten years between 1990 and 1999, studious released 28 comic films, and only 21 films that didn’t star Batman or a gang of mutated turtles. Throughout the entire decade of the 80s, there were only nine adaptations. In comics, it would seem, Hollywood has re-discovered a muse—one that may be the perfect fit for the new business model that that dominates big-budget film production.

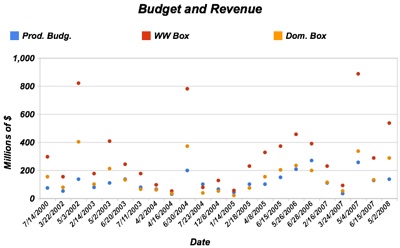

Over the next several weeks, I’ll be exploring many of the trends to be found in Hollywood’s current obsession with all things comic related. Just above is a graph of the production budgets, domestic revenues, and worldwide revenues of the 23 of the 34 films from the Comic Century that I’ve classified as "Superhero Films" (that is your “Spider Mans,” your “Fantastic Fours,” your “Ghost Rider,” and so on). Some very basic things jump out from this graph right away: on the whole, budgets of superhero films have grown since 2000. But so too have gross revenues, and for the most part, the money spent on these films has been spent wisely, as bigger budgets have correlated with bigger returns. As we’ll see in a later post, when looking at all the films from the Comic Century, that does not necessarily hold true.

There are a few points of order that I want to get out of the way before next time. Earlier, I referred to the two groupings of comic adaptations, pre-2000 and post, as different cycles. While I deploy the term cycle here to indicate renewed creative vigor and unity around a loose set of source materials (and not necessarily a set of generic conventions), some genre scholars may argue that the line I’ve drawn (at the year 2000) is too rigid and arbitrary to effectively delineate the flow of artistic energy and experimentation that dissipated at the end of the first cycle of comic book films, and increased during the second cycle. That is certainly a valid point. Some pre-2000 films (“Blade,” “Spawn,” and I’d even hear arguments for “Judge Dredd”), anticipate the comic book films of the 2000s, while others, like “Josie and the Pussycats” and “Men in Black II” likely belong grouped with the earlier cycle. But for the purposes of discussing business matters as they pertain to the Comic Century, I’ve found it most convenient to draw the line at “X-Men,” for reasons I will expand on further in a later post.

The facts and figures that I’ll lean on throughout this project were all culled from the website BoxOfficeMojo, which while heroic in its feats of data accumulation, may not be infallible. For now, it’s the best I can do until I nail down a cinema studies fellowship and quit my day job. While I feel very confident in the post-2000 data that I will use for the majority of this discussion, I know that there is the possibility that some films that do not appear in BOM's archive for whatever reason might be getting left out (the only notable among this group that I can think of off the top of my head is the 1989 Dolph Lundgren vehicle, “The Punisher”).

It’s important to note that I’ve limited myself to only films that have received a wide release, thus no “Ghost World” or “American Splendor.” And I’ve also limited this discussion to only those films that are adapted from comics. Thus no "Superhero Movie" or "Hancock." There is a discussion to be had about films that share many of the same generic elements as superhero or comic book films—like the aforementioned "Hancock" or Raimi’s “Darkman”—but that will have to wait for later. That discussion could also become part of a larger exploration of alternate media adaptations, as video games, like comics, have increasingly taken the place of books in the minds of film producers looking for a potentially lucrative property.

So that’s where we’re headed: it should be interesting. Tomorrow, “The Incredible Hulk” drops, and I’ll be breaking it down in the Box Office Special come this weekend. In the next installment of the Comic Century, I will be examining the changes we’ve seen in the nature of comic book adaptations in a post titled “Sweeping Out the Comic Clutter.”