The Others (Movie Review)

“The Others” is a film I have heard mentioned in several discussions on the shape of narrative cinema over the passed decade. And while I did see the film upon its initial release I never much had the urge to revisit it. I remember enjoying the experience but not quite recalling anything particularly extraordinary about it. However, revisiting the film 10 years after its release it is easy to see the potential and foresight displayed here. Not only is the film richly engrossing and stylishly produced, but it is also an adeptly crafted piece of genre filmmaking that utilizes its horrific elements to both titillate our bodies and provoke our minds.

Set in 1945 at a Jersey island manor, the film centers on Grace Stewart (Nicole Kidman) and her children Anne and Nicholas (Alakina Mann and James Bentley). Grace anxiously awaits the return of her husband Charles who may or may not have been killed while fighting in France. All the while she spends her days home schooling the children on Christian morals, the after-life and harsh punishments for denying Christ. Anne and Nicholas are also afflicted with a severe sensitivity to light, causing them to break out in blisters should they be exposed to any source much stronger than fire. Curtains remain drawn and doors locked to control the spillage of light around the house enshrining the manor in darkness and lamplight.

One night the Stewarts’ serving staff inexplicably disappears. Conveniently they are visited by a group of three strangers in search of work. What’s more, Mrs. Mills (Fionnuia Flanagan), Mr. Tuttle (Eric Sykes), and mute Lydia (Elaine Cassidy) claim to have worked for the manor’s previous owners. Upon the arrival of Mrs. Mills and company, it is revealed that Anne has been seeing four intruders visiting the house; young Victor, his mother and father, and an old crone of a woman. Highly suspicious of her daughter’s stories, Grace dismisses these claims as imaginary, insisting on keeping fantasy and superstitions out her children’s minds. But when Grace begins to hear footsteps, have doors violently close on her, and curtains opened she is finding not believing becoming increasingly more difficult.

Directed and written by Alejandro Amenábar, “The Others” is a film that explores the pain of solipsism, shifting morality and the dangers of fundamentalism as framed by the struggles of parenting. Throughout the film Christianity—more specifically the bible as an instructional text—is brought into conversations and teaching lessons. The film even opens on a black screen as we listen to Grace relating the story of creation from the Book of Genesis. From early in the first act we hear the children express their doubts and uncertainties of these stories, only having their beliefs reinforced by the threat of eternal pain. But as the strange apparitions increase the children begin to ask more complicated questions of their mother and her beliefs. When talking about the war, Anne asks Grace how they can tell who the “goodies and the baddies are.” Grace has no reply. The film has been accused of being anti-religious in nature, seeing Christianity as a draconian organization spouting lies. However such criticisms are far too literal and ignore the ways in which the film utilizes Graces’ religious views as being emblematic of her own view of the world. Rather Amenábar is making claims on the ephemeral role of parent as authority figure and the necessity of them to fade into the background.

Any discussion of the film needs to address the conclusion so if you haven’t seen “The Others” skip to the last paragraph. Throughout the film we hear Mrs. Mills having private conversations with Mr. Tuttle, each of them cryptically alluding to the “situation” in which they are in. After finding a funerary portrait and the gravestones of the three staff members, Grace makes the assumption that they are responsible for the occurrences. However, after locking them out of the house, Grace stumbles upon the old woman and Victor’s parents as described by her daughter holding a séance. Grace watches as her daughter, standing beside the old woman whispers into her ear. It is revealed that Grace had murdered the children and then took her own life. While the conclusion could easily have been a sloppily executed “Gotcha” moment, Amenábar handles it with a quite cool that maintains a substantial punch.

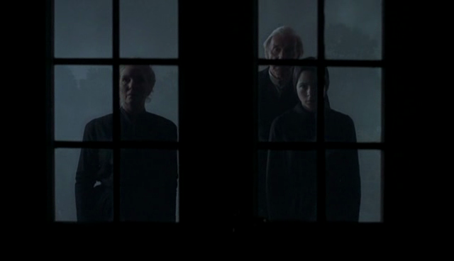

The reveal is an interesting narrative device in the sense it disallows the characters to change over time. While Grace eventually accepts her children’s words as truth and admits to having murdered them, the film concludes with an image of stasis, Grace, Anne, and Nicholas framed in a manor window watching the intruders leave. Mrs. Mills (and we can infer Lydia and Mr. Tuttle) is unable to live outside of her lived place and continues her role as servant, offering to make tea. The ghosts cannot change despite being given knowledge of their true nature. Rather, they are left to continue living the lives full of mistakes and regrets. The fact the entire film is presented to us from Grace’s subjective perspective that they are still alive is a gesture which further alludes to the aforementioned themes of enclosed perspectives denying the influence of the outside world. We are given the satisfaction of narrative development but it is a conclusion that refuses the characters to live outside of themselves just as they had in life.

If the film has a weak point it is in how heavy-handed some of the visual symbolism can be. Aesthetically speaking the lack of light provides Amenábar with some beautiful graphic representations of Grace’s psychological state and the lack of “truth” within the house (i.e. the family). But at times these moments have the tendency to feel overly manufactured and convoluted. That being said “The Others” is still one of the more interesting and unique horror film experiences of the past decade; a beautifully crafted piece of cinema that should endure with time.