The Killer Inside Me (Movie Review)

“The Killer Inside Me” walked a long and twisted road before it made it to the screen in its current incarnation. Jim Thompson’s 1952 novel is considered one of the high points of pulpy noir fiction and no less an authority than Stanley Kubrick called the book, “"probably the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered”. Shortly after it was written, a first attempt at making a film adaptation got under way starring Marlon Brando as Lou Ford, the titular killer deputy sheriff, and Marilyn Monroe as Joyce Lakeland, the S&M loving prostitute.

Plans for that film fell through after Monroe’s death and the project lay dormant until the 70s, when a version starring Stacy Keach was made. While Keach was right for the role, the cheesy 70s TV-movie vibe lost much of the grit and grotesqueness of Thompson’s novel. In the mid-90s, Thompson’s books were rediscovered and interest renewed in making a proper film version of “The Killer Inside Me”. A few iterations starring actors like Tom Cruise and Leonardo DiCaprio made it to various stages of pre-production but maybe the most intriguing almost-was would be Quentin Tarantino’s take, starring Brad Pitt and Uma Thurman, which was ultimately scrapped after 9/11 due to the excessive violence.

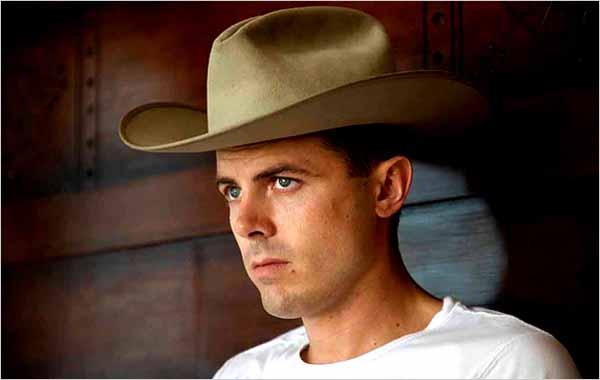

In 2010, almost ten years after the original paperback was printed, “The Killer Inside Me” got a faithful adaptation. This take, directed by Michael Winterbottom, stars Casey Affleck as the soft-spoken psychotic sheriff Lou Ford. At the movie’s open, Ford keeps his inner demons buried deep inside. He’s a deputy sheriff in a sleepy Texas oil town who dates a pretty, good-hearted girl named Amy Stanton (played by Kate Hudson). One day when Ford is sent to have a few words with a low rent prostitute named Joyce Lakeland (Jessica Alba), things get heated and something snaps inside Ford. He begins beating Joyce, but it turns out that she’s into that kind of thing just as much as he is. Soon enough, Ford is regularly visiting Joyce and as he expresses his long-suppressed violent instincts, he starts to crave even more. He and Joyce cook up a scheme to extort some money out of the son of a rich man but at the last minute Ford double crosses Joyce, beating her savagely and shooting the rich man’s son, intending to make it look like they killed each other. Joyce survives in a coma however, and many other people in town, including the district attorney, aren’t quite buying Ford’s story.

“The Killer Inside Me” is a quintessential “through the eyes of a serial killer” story. You know Ford is a bad guy, you see him do bad things, he isn’t even particularly likable but still, despite your best intentions, you can’t help but hold your breath in anticipation when he nearly gets caught and breathe a sigh of relief when he weasels his way out of another situation. “The Killer Inside Me” is to small town 1950s America, what “American Psycho” is to 1980s Wall Street. Much like Patrick Bateman, Lou Ford has a thinly veiled mask of normalcy that hides unspeakable evil and madness and as that veil lifts, little by little, Ford brazenly defies the rest of the world to stop him. Casey Affleck turns in a fantastically low-key performance that uses his boyish looks to his advantage in order to create an all too believable mass murderer next door.

While it’s far from a splattery horror movie, “Killer” does have some shocking scenes of brutality, particularly of Ford savagely beating women to death. Thankfully, there’s nothing to match the hard-to-watch violence of recent shockers like “Irreversible” or “Martyrs” but there is some pretty explicit woman-beating which will probably be enough to turn many people off this film. These scenes are made even more shocking by the fact that they come as violent punctuations to the otherwise slow, simmering pace of the film.

Ultimately, Winterbottom’s take on “The Killer Inside Me” is satisfying and well-acted, although it’s a little too flat and uneven to become the instant exploitation noir classic that the source material could be adapted to in the right hands. If nothing else, it shows that despite what endless baby boomer nostalgia might lead us to believe, in the good old days people were probably just as screwed up as they are today, they just hid it better.