Skew (Movie Review)

It’s apparent that the nearly consistent 15 year long presence of “found-footage” and subjective camera POV visual aesthetics in film and television (FFSC from here out) has tapped into a certain type of audio-visual experience that connects with viewers. Though at first glance we could write off these stylistic techniques as cash-grabs it is surprising that the novelty of such techniques has continued to raise more eyebrows in curiosity rather than skepticism. We see FFSC in a wide range of production circles including independent films, international productions, television shows, and larger Hollywood bankrolled films. And while an admittedly small portion of media utilizes this aesthetic, the legs and stubbornness of these productions will leave a resounding mark when future generations look back at the first decade of cinema’s second century.

Sevé Schelenz’s film “Skew” is yet another entry into this cycle of films. Filmed over the course of several years, starting in 2005, “Skew” finally saw a “Watch Instantly” release on Netflix late last year and has been making the rounds of genre festivals for the past year. And while this may provoke images of choppy, hackneyed low-fi video work, what we get is a rather intriguing and well thought-out take on how the FFSC model can work in unique and interesting ways outside of more traditional 3rd person perspective filmmaking. Rather than simply laying this model over a genre narrative the film also becomes about the aesthetic itself.

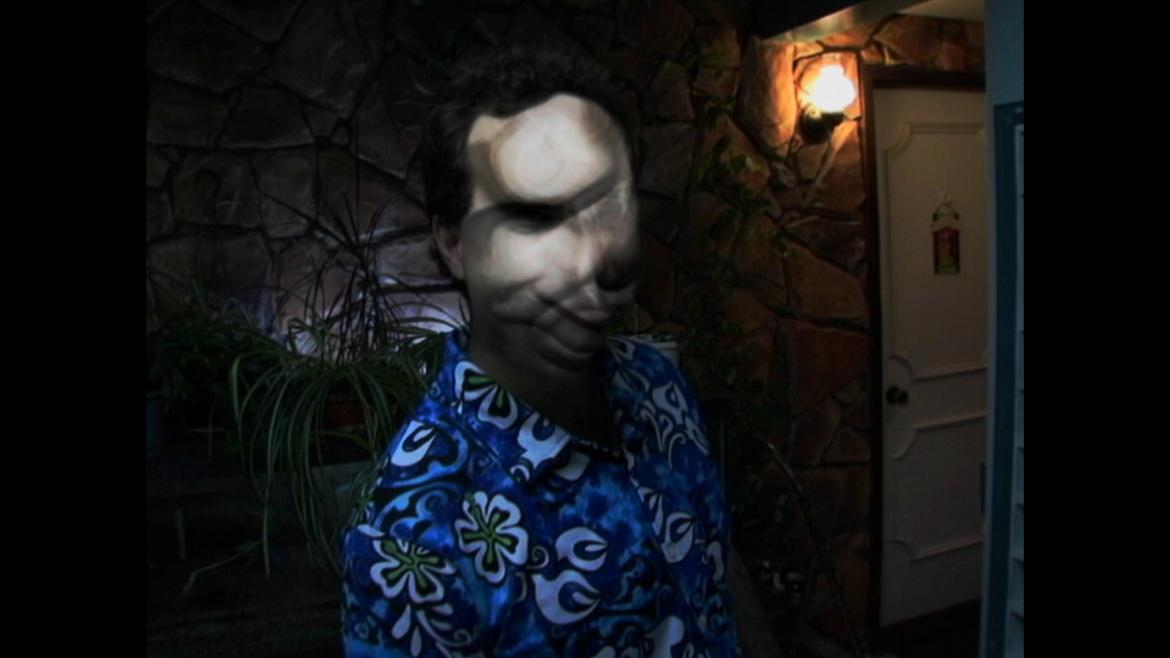

“Skew” begins as Simon, his best friend Rich, and Rich’s girlfriend Eva (Rob Scattergood, Richard Olak, and Amber Lewis respectively) embark on a road trip destined for the wedding of a mutual friend. Along the way, Simon records with a small video camera, documenting the trip and asking his friends the sort of silly banter questions you can expect. Rich and Eva entertain Simon’s documentary impulse for a time, putting on a sufficient enough show to appease him. When asked about his girlfriend Laura or other factors of his personal life, Simon skirts the questions with an awkwardly glib line or sarcasm. But as the trip continues Simon begins to notice strange images showing up through the viewfinder of the camera. Strangely, people whom the trio have run across during the trip begin to show up dead, prompting the trio to question whether or not they should continue their trip amidst the ill portents. Soon the tight confines of the car, Simon’s increasingly strange behavior, incessant filming, and personal conflicts become more than what the three can bear.

While the setup is undoubtedly threadbare “Skew” finds a spark of originality in the use of its subjective view. Rather than allowing the characters to accept the filming process as something that just “is”, Schelenz attempts to build confrontations and examine character histories and motivations through the act of recording. Simon reveals that the camera and process of recording for him is about capturing the immediacy of those formative moments in our lives that he had missed out on in his youth. In a way, Simon becomes our surrogate in more ways than one. First, there is the literal sense in how the audience shares his video-filtered perspective. Secondly, we can view how Simon relies so heavily on technology to create memory and retain identity as a commentary on the current state of technology in our social lives. Then, as the film continues we learn that the act of filming is having some unintentionally dangerous results. This results in an interesting feedback loop between Simon’s inability to stop recording and the film’s own reliance on recording to exist, further accentuating the cyclical desire for and repulsion by technological interference. It’s a juicy move that provides some interesting musings on our relationship to media filtered social worlds and constructed identities.

But while I admire much of what is going on here, there are a few shortcomings that keep the film from being great. Firstly, we encounter a number of pacing problems that undermine the previously mentioned notions of mediated experience. To convincingly pull off the technique a certain amount of dead time and space is needed because the aesthetic is predicated upon the idea of capturing something unbelievable by chance. But in order for “chance” to be believable we have to accept the apparent unadulterated nature of the footage we see. However, we are taken out of this state a number of times by strategically placed tape skips, sound dropouts, and the fact the film rewinds itself on several occasions. While these techniques work well when used sparingly they tend to be relied upon a too much especially toward the film’s third act, a process which severely hampers a number of the “scares”. The film is also hampered by a few rather odd-looking effects moments, a poorly placed unrequited love story, and relationship trouble that doesn’t seem to go anywhere accept to provoke a fight or two.

It seems to me that the process of discussing FFSC films requires a different set of criteria that critics haven’t quite come up with yet. Certainly there will be constants when it comes to film criticism. But it is also essential that we recognize and admit when the rules of viewing a particular film let alone an entire cycle of film production requires us to rethink how we relate to the characters and also to the film as an object in and of itself. Indeed, FFSC foregrounds and highlights the act of watching private, personal material, presented as unstructured and spontaneous. When comparing these types of films to the popular reemergence of 3D technologies it is apparent that questions of realism, authenticity, formal structure, and self-awareness are running wild in media. What I find particularly interesting about these trends is how specific they are to our current historical moment. These are very much films of the “Information Age” that could only have been made possible by the emergence and growth of video and digital technologies. “Skew” is a film very much aware of this tendency, and it articulates the horrific unintentional results of a technological age where mediated experience becomes the real.