In Extremis: A Legal Analysis of A Nightmare on Elm Street

Editor's Note: Team BGH welcomes Adam as our newly established legal correspondent! Adam has been on retainer since he selflessly offered his expertise pro bono regarding Joe's Beer Gutz segment on Episode 434: Squirm. He continues to make our decisions regrettable and reminds everyone to never, ever listen to our advice. In Extremis will cover all your burning legal plot hole queries from horror cinema. Example topics include but are not limited to, “Are blobs people in the eyes of the law?” or “Is the creature from The Thing just gerrymandering?”. This time Adam takes a look at the dubious legalities of the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise

A “Legal” Analysis: Freddy and the Unwarranted Technicality

Disclaimer: This Review Contains Spoilers for a 34-year-old film and other films in the series. This is also legal entertainment and provides no legal advice. I am also a Solicitor in Canada, so my knowledge of US State and Federal law is likely less than Ted Bundy’s.

You awake with a jolt from a nightmare. The killer was a boiler-room butcher that used his passion for fashion to weld/sew/glue gun (?) silverware to a glove; a murderous combination for any kid sleeping on Elm Street. You know the story so well that you are not even surprised when he appears at the end of your bed as a TV snake.

But then he pulls out a laptop and you look on in abject horror: ANOTHER REVIEW OF THE A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET FILMS. Truly this is the Final Nightmare… wait they already did that. I guess this is the ULTIMATE LAST CONCLUDING ENDMOST FINALEST NIGHTMARE!

As the completely unofficial lawyer of Bloody Good Horror, I am here to analyze the age-old question raised by the Nightmare franchise: How does a person that killed 20 children, his step father, AND his wife while his daughter watched, get released on a technicality?

The short answer is: He Doesn’t.

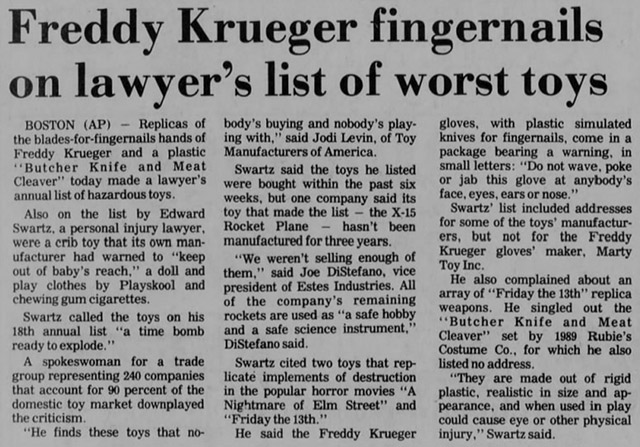

Freddy Krueger is released in the first film, A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), because “SOMEONE” and they never actually say who, did not sign a warrant in the right place. Where were they signing? In the middle of a paragraph?

We are told by one of the greatest drunks in film history Margaret Thompson, Nancy’s Mother, that “the lawyers got fat and the Judge got famous, but someone forgot to sign the search warrant in the right place and Krueger was free.”

Well, I am not sure how a lawyer gets rich off defending a power plant worker with no discernible assets, but perhaps Freddy sold his gloves on a proto-Etsy. Well, because of the justice systems failure, vigilante justice turned him into the pun spewing teen murderer you know and tolerate.

Assuming only the information we have from the first film is true, then the search warrant would likely be valid even if it is not signed. The Tenth Circuit Court recently decided in United States v Cruz,* that the fourth amendment, which protects citizens against unlawful search and seizure, does not per se require the signature of a warrant. The Court determined that while it may be more difficult to prove that a certain judge issued the warrant, there is no constitutional requirement that a judge sign a search warrant. The requirements for issuing a search warrant are: 1) that there is probable cause to search a place (more likely than not that evidence will be found in a specific place); and 2) the scope of the search is set out with specificity (it is clear what and how you are searching).

Nightmare takes place in Springwood, Ohio, a not surprisingly fictional town. Ohio falls under the sixth District Circuit Court and Cruz was a Federal Tenth Circuit Appeal Court decision. This new decision is not binding in Ohio, but it is persuasive and any judge is going to take that case and other cases that state similar things into account when deciding to free a SERIAL CHILD MURDERER.

But Adam, you might say, this is only one way the story was told. There have been 19 different writers that have had a chance to mess up the storyline (including the remake and Freddy vs. Jason) of Freddy’s origin; and that is just in the films.

In Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991), we find out that Freddy killed his abusive foster father, as well as his wife Loretta, in front of his own daughter, when she found out he killed the children of Springwood. Now, although his daughter promises not to tell, she could be compelled to testify under oath, and presumably the police could get a warrant to Mr. Krueger’s house when his wife went suspiciously missing as he was being investigated for serial murder.

This film mentions that the Judge in Freddy’s case was drunk at the time of the proceedings; i.e. his court case. And we all know from the children’s rhyme that every time a judge drinks, a serial killer gets set free. Except that this would result in a mistrial. If the judge was drunk when they heard the case or gave instructions to the jury, the matter would be appealed and then heard by a different judge. If the Judge was drunk while issuing the warrant, then there might be a case for the warrant being illegal, but it would depend on what the Judge understood while making a determination on probable cause to search; i.e. was he wriggity-wriggity-wrecked or just sloshed.

Further, the story goes that the officer that arrested Freddy did so at the time that Freddy had kidnapped and was currently threatening the officer’s daughter. Accordingly, a lawful arrest could be made for kidnapping and a search could be done to protect the officer’s safety and from the possible destruction of evidence. Therefore, the officer would not need a warrant search to search Freddy and his immediate surroundings (i.e. the boiler room that is likely chock full of evidence).**

The first episode of Freddy's Nightmares (1988-1990) stated that Freddy got off simply because the arresting officer failed to read Freddy his Miranda rights. The Miranda Warning is the right to silence warning given by the police in the United States when the suspect is in police custody before an interrogation. This is done to preserve the admissibility of their statements against them in criminal proceedings i.e. confessions. Basically, if Freddy confessed and he was not warned about his right to silence, an attorney, etc. then anything he SAID could not be used as evidence. But the fact an officer saw him attacking a child, along with Freddy’s glove that matches the slash marks on the murdered children, and anything else incriminating that the police found in the boiler room, are all good evidence he might not be the squeakiest of cleaners.

That bring us to the novelization of Freddy vs. Jason… you heard me. Someone thought that the screenplay that gave us Freddy playing pinball with Jason Voorhees, needed to be expanded upon in a novel.

We must give a hand to the writer (Stephen Hand), who gets the closest to making the story of Freddy’s release logical. In that story, a cop broke into and trashed Freddy’s house finding his trophy room, prior to going to the Boiler Room at the powerplant, and arresting Freddy. The United States has the fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine that all evidence deriving from an unlawful search is inadmissible.*** Therefore, all the evidence found in the house would likely be excluded, and a judge would need to determine if the subsequent arrest and search were significantly connected to the illegally obtained evidence. We simply do not know what evidence the police had. However, there may be a separation between the illegal activity (breaking into a suspect’s house) and the discovery of evidence (at a separate location where someone is currently murdering a child). Likely a court may err on the side of allowing the evidence obtained at the boiler room into Freddy’s trial.

In the comic book Freddy vs. Jason vs. Ash: The Nightmare Warriors (2009), an FBI Agent named Wesley Carter travels back in time to 1964 to sign the warrant, preventing Freddy from being burned by the local parents, and therefore stopping his entire origin. Ironically, in this case it is possible that this could lead to Freddy’s acquittal as the FBI officer is acting without authority in forging a signature on a warrant; but that would be a matter for Rick and Morty’s Time Court.

The 2010 remake of A Nightmare on Elm Street, does not really get into the explanation for why Freddy was released. That may have been the only good part of that film.

In conclusion, the evidence against Freddy would be admissible and outside of the world’s most/least sympathetic jury, he never would have been a free man. However, without this get out of jail free card, we would have no third-degree burns, no dream murder, and no deplorable puns… and that is the worst PUNishment of all.

Overall, I give the Nightmare on Elm Street Series a 2/10 for Legal Realism, and a 5/9 for which of the films I would re-watch (1, 3, 7, 4 and Freddy vs. Jason, in case you were wondering).

Footnotes

*United States v. Cruz, 774 F3d 1278, 1284-85 (10th Cir. 2014),

http://www.ca10.uscourts.gov/opinions/14/14-2017.pdf;

and also citing:

United States v. Lyons, 740 F.3d 702, 724 (1st Cir.), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 2743 (2014)

**United States v. Robinson, 414 U.S. 218 (United States Supreme Court 1973); modified by subsequent cases relating to vehicles and cell phones.

*** Fruit of the Poisoned Tree Opinion, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fruit_of_the_poisonous_tree

Also, helpful in my research:

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/OffOnATechnicality