Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Movie Review)

Today it seems that notions of distinct national cinemas are becoming increasingly difficult to argue for. I do not mean to say that particular narratives and cultural contexts are disappearing nor are they ceasing to inform particular film cultures. Rather, I am thinking more along the lines of how certain cinematic techniques for conveying information to us are becoming less divergent across filmmaking communities. Over generalizing blanket statements? Absolutely. But there is no denying that not only has the concept of nationhood undergone much rethinking but then there is also the simple matter of the pervasive access to films many have (though certainly not most). The prevalence of online streaming options, the ability to pirate films before they are even released, and other video technologies grants nearly any screen with internet access the potential for becoming a viewing device. The spread of not only narratives but also the formal ways in which films are shown to an audience are allowed an ever widening exposure to locales previously incapable of seeing films from across the globe thus informing a greater swatch of filmmakers. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is a film that proves to be a fascinating platform from which questions of national identity, personal vision, and cinema as art connect. The latest from Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Uncle Boonmee’s framing narrative centers on the experience of its titular character slowly succumbing to kidney failure. Boonmee’s sister-in-law Jen and a younger relative named Tong accompany Boonmee back to his farm in the northern Thailand countryside.

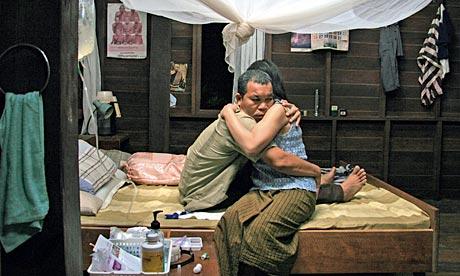

One evening over dinner the three are joined by the ghost of Boonmee’s dead wife, Huay, and Boonmee’s estranged son Boonsong who has been transformed into a monkey spirit complete with total body fur and red glowing eyes. What follows are a serious of vignettes in which Boonmee ponders the reasons for his illness and thinks on the connections he has to various landmarks—sensory and physical—that he encounters around the farm and the surrounding countryside. We watch as flashbacks to seemingly unrelated stories are intercut with Boonmee’s home healthcare at the hands of Jen and his dead wife, ostensibly showing us the instinctual passed memories of his former lives as human, animal, and spirit. Uncle Boonmee is a sweetly tender and haunting film that resists any clear criticism. Rather than focusing on the interpersonal relationships of its characters, the film is more interested in creating a mesmerizing experience of cinema-time akin to some of Tarkovsky’s films (“Stalker” and “The Sacrifice” come to mind most clearly).

Admittedly I know as much about Thai history, culture, and Buddhism as I do Martian topography so I’m coming at this film from a completely outside perspective. But in a way not having a frame of reference for the film’s particulars seems somewhat non-essential in grasping the affects that Weerasethakul is going for (though such a frame would provide a more enriched experience). Throughout the film the characters speak to one another in a manner that neatly conveys whatever may be going on internally; flatly expressing their current psychological states. And while this at first seems overly severe and perhaps lazy, it becomes apparent that these acts are a declaration of clarity that only comes about through the very real presence of impending death or transformation in our lives. The film’s continuous use of long, locked down shots further accentuates this point. The camera becomes an instrument for conveying presence and personal awareness more so than a stylizing tool of sensation. Uncle Boonmee is also a film that feels catered for a certain kind of Euro-American “art” cinema crowd. With its long, languid shots, ponderous pacing, obsession over the nature of existence and the ethereal in the quotidian, one could argue that it is representative of a particular category of film that is consistently lauded by critics of Western-Euro film societies since the emergence of film festivals, schools and the first real “art cinema” movements of the 1950s. Indeed, the film won the Cannes Palm d’Or in 2010. It is also unsurprising that Weerasethakul studied film at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. And while I appreciate Weerasethakul’s approach throughout most of the film, there are times in which he seems to be reaching into the bottom of the kitchen sink for material or stylistic choices. Some of which seem to come up short, not quite working in conjunction with the rest of the film.

For example, during the film’s “climax” (I use that term very loosely) the director presents us with a bizarre montage of still photography that at once seems to be a compliment to the voiceover but which also almost seems to be post production photos. While I have no problem with a film calling attention to its artificial nature, the gesture seems somewhat uncertain of itself, not entirely sure what it is trying to counterpoint in the accompanying voiceover or in the films thematics as a whole. What I do find particularly mesmerizing about this film is how we can also view it as kind of anti-western-horror film. Rather than mourning and violently resisting loss of individuality, mercurial transformations, and the unknown, Uncle Boonmee embraces these concepts and finds great comfort in transient identities.

When the film works, the images and tonal beats that Weerasethakul creates are some of the most affecting I’ve seen in a long while. It certainly is a film that sticks with and asks you some rather uneasy questions. But I also cannot help but feel that it panders too much to an art house crowd, aping some stylistic elements and tendencies that in other contexts might seem a touch trite and pretentious. That being said, Weerasethakul’s experiments with shot duration, physical space, and narrative time create a rich and bittersweet experience that is a uniquely divergent voice for those of us who are often told to be frightened of these transformations.