Bug (Movie Review)

"Bug" is a prime example how poor marketing can destroy a film's chances to find an audience. The ominous voice in the trailer drones, “They live in your blood... and they feed on your brain. This spring from the Academy Award winning director of the Exorcist comes the movie the Chicago Tribune calls 'one of the most disturbing horror movies imaginable.' Bug.”

What do you expect from that description? A body horror film about tiny insects that infect people and eat them from the inside out? A modern-day take on “The Exorcist” where possession is updated for the age of bio-terrorism and demons are swapped out for a killer virus? How about a psychological character-driven adaptation of a play about two lonely, damaged meth-heads who slowly go crazy together in a dingy hotel room? I'll give you a hint – it's not the first two. In fact, the trailer isn't just misleading, it's flat-out wrong. According the DVD box, the pull quote they used came from the Boston Herald, not the Chicago Tribune. Great job, Lions Gate.

The deceptive advertising was only made worse by the fact that some screenings of the film were preceded by the first five minutes of “Hostel: Part II”, and that the film's poster bore a distinct resemblance to the iconic posters for the “Saw” series. The end effect was that mainstream horror audiences who turned out for “Bug” in cinemas were justifiably angry at the bait and switch, and the arthouse crowd who might have been more appreciative of the film mostly wrote it off as a conventional horror film.

Whatever “Bug” is, it's certainly not conventional. Even the director, William Friedkin, has described it as more of a “black comedy love story” than a horror movie. “Bug” has a bit of stabbing and squirmworthy gore, as well as some disturbing imagery, but most of the horror elements are of a much more psychological nature.

Ashley Judd plays Agnes, a small-town bartender who has seen better days, who now uses drugs and alcohol to drown her pain at having her son be abducted at a supermarket many years previous. As the film starts, Agnes has been receiving mysterious calls from a silent caller which she attributes to her recently paroled wifebeater of an ex, Jerry (Harry Connick, Jr). One night after work, her friend RC comes over to the run-down hotel room Agnes lives in for an all-night booze and coke binge and brings along an acquaintance, a quiet, awkward drifter named Peter (Michael Shannon). To stave off her loneliness, Agnes invites Peter to stay the night and in short order the two get to know each other and end up in bed together. Peter reveals that he is AWOL from the military and that when he was serving in the Middle East he was subjected to some unusual experiments. He's convinced he's a part of a government conspiracy and in due time Agnes comes to believe him.

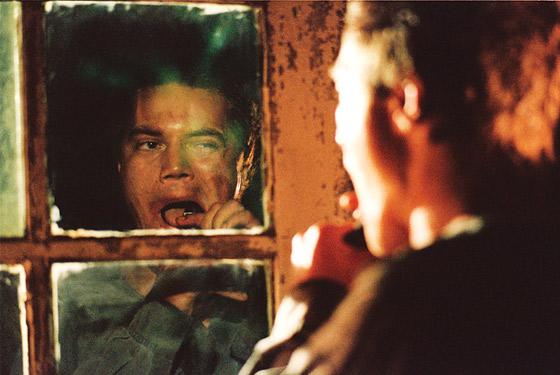

The rest of the film gradually ratchets up the paranoia Peter and Agnes feel until the living nightmare of the third act where the two cover every inch of the hotel room with aluminum foil, cringe at the sound of black helicopters overhead - which may or may not be just the ceiling fan - and gouge away at their bodies to remove the bugs they are convinced are living under their skin. The film leaves itself open to a number of interpretations and often leaves the viewer as unsure about the line between reality and imagination as its two main characters are. In the immortal words of Rick James, cocaine (in addition to crystal meth, pot, booze and crack) is “a hell of a drug”.

In stage-to-screen adaptations, the conventional wisdom is to open everything up and introduce new settings and more characters. Here however, Friedkin realizes that the zoom works both ways, and has taken the opposite approach and moved in closer and tighter than a play ever could. Ninety percent of the movie is set in three rooms and the actors are often shot in extreme close-ups, with no make-up to hide the bags and creases and sweat on their faces. The two leads turn in performances that are intimate, heart-breaking and disturbing all at once. With a slow journey into madness like this, acting too frantic too early could break the viewers suspension of disbelief and cause the whole movie to descend into hysterical goofiness. Thankfully, that's not a problem here.

As the marketing snafus demonstrated, “Bug” is a hard film to pin down. It does have strong body horror elements that would not be out of place in a Cronenberg film, but all of that is secondary to the real story. Agnes is a shattered woman who has little sense of herself and instead adapts to various roles depending on who she's interacting with. Peter is a sick man who is convinced that the entire world and his own body is conspiring against him. When these two lonely people's worlds collide, instead of the typical uplifting Hollywood story of love triumphing in the end, it turns out they're much worse off for having found each other and would have been much better off if they'd never met.

So is “Bug” a horror film? I'd say without a doubt it is. In this case, the madness of the characters isn't focused externally onto unwholesome acts like, say, chopping up co-eds, but instead is turned inside out, destroying its hosts from within like a parasite.