In Extremis: Genocide Tribunals and La Llorona

Disclaimer: In Extremis is a legal entertainment column that seeks to examine questions and portrayals of the law in horror films. Instances of genocide and sexual violence are discussed below.

La Llorona (2019) is a reconceptualization of the Latin American folk tale through the horrors of the real life Ixil-Mayan Genocide in Guatemala. The Guatemalan Civil War (1960 to 1996) created political instability and between 1981 and 1983, a counterinsurgency campaign began, causing the deaths of nearly 1,800 Maya Ixil Indigenous people, forced displacements of tens of thousands, and crimes such as rape and torture with impunity. One of the sites of a massacre was La Llorona, a small village outside of El Estor, a coincidence that may not have been lost on the filmmaker.(1)

Written and directed by Jayro Bustamante, La Llorona takes place after the events of the “Silent Holocuast.” The film comments on how society addresses supreme violations of human rights. La Llorona ultimately rectifies the outcome through spiritual intervention, but do you know what would have made such a gripping film more compelling? If they had stopped for about an hour and explained the terrifying legal implications of the actual case the film is based on.

General Enrique Montevardo (Julio Diaz), one of the film’s leads, is a direct parallel of General Efraín Ríos Montt. The former dictator of Guatemala, Montt was convicted and sentenced to thirty years for war crimes and fifty years for genocide on May 10, 2013.(2) This was a landmark win for human rights organizations, as it was the first conviction for genocide of a former head of state by a court in their own country. However, it was short lived as ten days later the constitutional court of Guatemala overturned the decision based on procedural issues, sending it back for a retrial before a separate tribunal. After a series of delays and legal rulings, including a psychiatric finding that Montt was suffering from dementia, his retrial began in 2017. General Montt died of a heart attack in April of 2018 before the determination of the second trial.

We must define the term genocide to understand how the court reached its decision. The UN in Article II of the Genocide Convention states:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

1. Killing members of the group;

2. Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

3. Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

4. Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

5. Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.(3)

This means that there must be a mental element of intending to destroy a portion or entire national, ethnic, racial or religious group and a physical element of one of the listed actions.

Proving a person committed genocide is extremely difficult for myriad reasons. First, there is the issue of standing (being able to bring the action). In 1999, Rigoberta Menchú, a Nobel Peace Prize winning activist from Guatemala, and others brought claims in the Spanish courts against Montt and other senior officials.(4) They alleged there was targeting of the Mayans as an ethnic group through genocide, torture, terrorism, summary execution, and unlawful detention. While some of the offences included Spanish citizens living in Guatemala, some claims happened solely in Guatemala to Guatemalan citizens. The lower courts held that there was no ability to bring the claim as it was outside their jurisdiction; clause 8 of the Convention on Genocide, directs an individual state not to exercise jurisdiction and to direct the matter to the United Nations.(5) On appeal, the Constitutional Court (the highest) overturned the decision in part, interpreting Article 23.4 of the Organic Law of the Judicial Branch (LOPD) to allow the claim.(6) Article 23.4 granted standing for offences like genocide and terrorism committed by non-Spanish persons. The court noted that the law must be broad enough to allow these types of claims to prevent nations from protecting individuals with impunity when they refuse to prosecute.(7)

Second, there is the issue of extradition and impunity provisions. The Spanish hearing requested extradition, but the Guatemalan court denied the request.(8) In 2007, Montt was elected to a seat in Guatemala’s Congress. This provided him immunity from suit (civil and criminal claims) without his consent--a more extreme version of the qualified immunity seen for the police in the United States. Montt’s term ended in 2012 and he was declined amnesty for genocide charges by Judge Miguel Angel Galvez, noting that the 1996 National Reconciliation Law prevented amnesty from crimes against humanity and genocide charges.(9) The Supreme Court eventually overturned this decision.

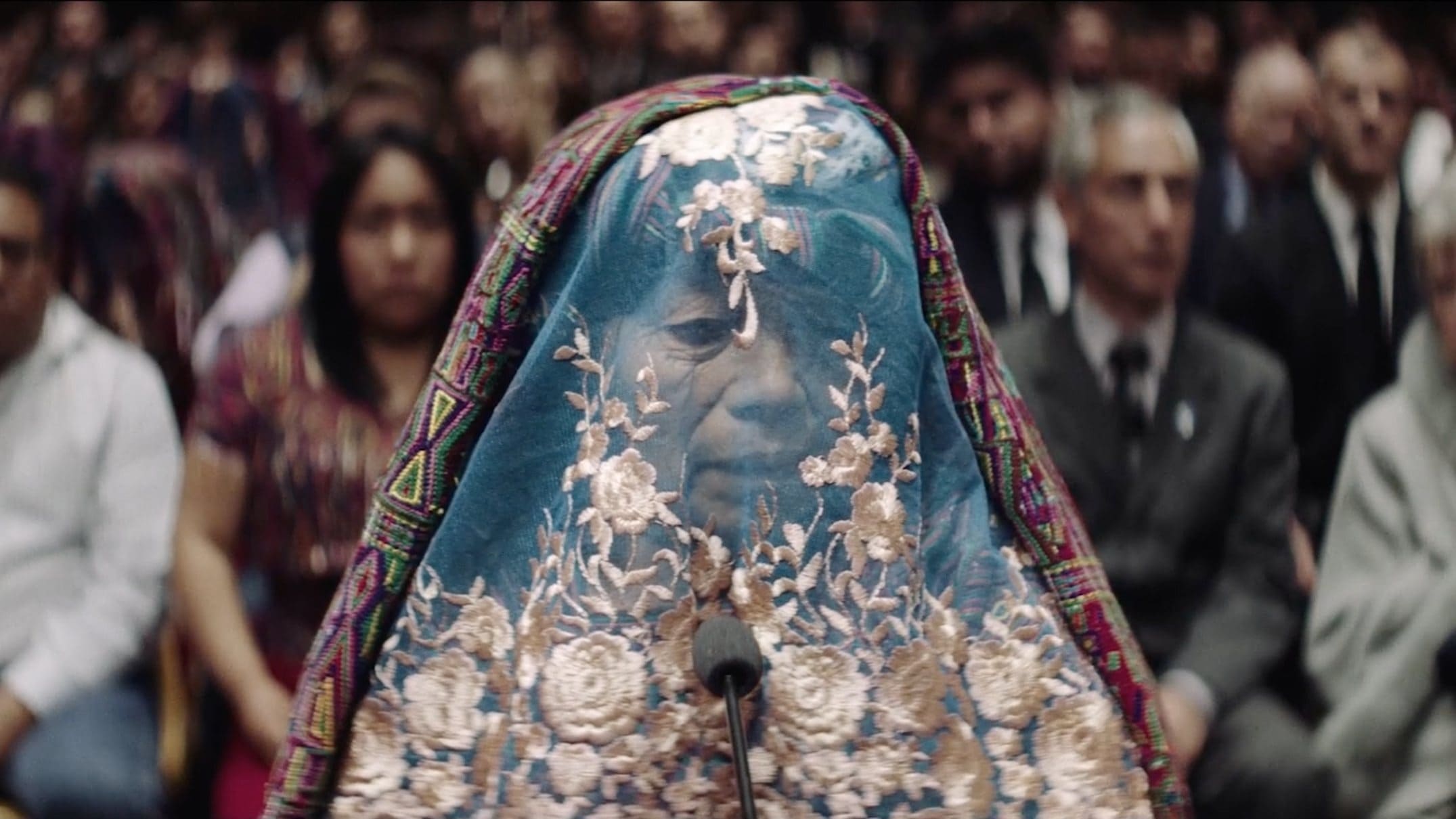

Third, is the length of the various proceedings. In Guatemala a hearing began before the Tribunal Primero A de Mayor Riesgo (Tribunal Primero A) on March 19, 2013. On the first day, Francisco García Gudiel, counsel for Montt, tried to have two of the three judges recused based on bias against him; this led to his ejection from the courtroom.(10) The court heard the matter over 27 hearings, including reviewing evidence from a 1983 documentary film, When the Mountains Tremble. Montt confirmed in video footage that he had full control of the military at the time of these actions and that “there is an enemy in every man, woman, and child.” This and further evidence was extrapolated to meet the mental element of genocide.(11) More than 90 survivors and various experts testified before the court about displacement, famine, infanticide, wartime sexual violence, and targeted killings, meeting the physical components of genocide. Judge Barrios in the decision held that Montt had “full knowledge of what was happening and did nothing to stop it—having the knowledge of the events, and the power and the capacity to do so.”(12)

On appeal, the Constitutional court annulled the decision based on denial of Montt’s due process as his counsel’s ejection from court left him temporarily without a legal defence.(13) Also, the court accepted the constitutional challenge that the Tribunal Primero A had not complied with the orders of the Appeals Court, despite that court issuing a decision the day before the verdict that the Tribunal complied. This is a surface level analysis of the proceedings and for detailed analysis, please see the following sources.(14)

Now imagine that you faced violence in a targeted attack to exterminate your ethnic identity. You wait 20 years to have the matter heard in Spain and then you wait 10 more years to have the matter heard in your home country. You testify in front of the perpetrators and the nation, receiving veiled threats and public advertisements that say you are lying.(15) The dictator’s conviction is brief and he is on house arrest, based on mild procedural issues that had no substantive effect on the outcome. You would have to testify again, with no guarantee that it would make a difference, and with more challenges and Montt’s death, that trial never came. Would you not want a ghost to have haunted that man and the family who justify his actions?

There is a level of rage imbued in La Llorona by this historical context and it deepens the scenes of testimony to a soul sucking sorrow. The film is resonant and scary. Bustamante continuously uses slow pull out shots to focus your attention on the impact of the dialogue and to allow negative space in the background for your eyes to investigate. Despite the film’s supernatural leanings, it knows that real life is always more terrifying than a movie. I cannot recommend this film enough. 10/10 legal realism; 9/10 for the film.

- Knowlton, A., Q’eqchi’ Mayas and defense of territory : learning through the contentious politics of land in “post-conflict” Guatemala, T, University of British Columbia, 2016, doi: dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0340561.

- Rigoberta Menchu et al. v Rios Montt et al, Constitutional Court of Guatemala, Tribunal Primero A, Case No. Exp. 1904-2013, 20th May 2013.; the decision is 718 pages and I have been unable to find a published version online and in English for a full review.

- UN General Assembly, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 9 December 1948, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 78, p. 277, available at: www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3ac0.html. Accessed 25 January, 2021.

- Roht-Arriaza, Naomi. "Guatemala Genocide Case. Judgment No. STC 237/2005." The American Journal of International Law 100, no. 1 (2006): 207-13. Accessed January 25, 2021. doi:10.2307/3518840.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- ICD. “Rigoberta Menchu et al. v Ríos Montt et al”., (2013), online: ICD - Ríos Montt - Asser Institute <www.internationalcrimesdatabase.org/Case/948/R%C3%ADos-Montt>; Spanish Court Documents: www.asser.nl/upload/documents/DomCLIC/Docs/NLP/Spain/Guatemala_Constitutional_Court_Decision_10-12-2007_Part1.pdf; www.asser.nl/upload/documents/DomCLIC/Docs/NLP/Spain/Guatemala_Constitutional_Court_Decision_10-12-2007_Part2.pdf

- Human Rights Watch. “Guatemala: Ríos Montt Trial a Milestone for Justice”, (28 January 2013), online: Human Rights Watch. www.hrw.org/news/2013/01/28/guatemala-rios-montt-trial-milestone-justice. Accessed 25 January, 2021.

- Burt, Jo-Marie. “Historic Verdict in Guatemala's Genocide Case Overturned by Forces of Impunity”, online: NACLA. nacla.org/news/2013/6/17/historic-verdict-guatemala%e2%80%99s-genocide-case-overturned-forces-impunity-0. Accessed 25 January, 2021.

- When the Mountains Tremble, ed (Guatemala: Skylight Pictures, 1983).

- Burt, Jo-Marie. “Historic Verdict in Guatemala's Genocide Case Overturned by Forces of Impunity”, online: NACLA https://nacla.org/news/2013/6/17/historic-verdict-guatemala%e2%80%99s-genocide-case-overturned-forces-impunity-0. Accessed 25 January, 2021.

- MacLean, Emi. “Guatemala's Constitutional Court Overturns Rios Montt Conviction and Sends Trial Back to April 19”, (14 September 2020), online: International Justice Monitor. www.ijmonitor.org/2013/05/constitutional-court-overturns-rios-montt-conviction-and-sends-trial-back-to-april-19

- ICD. “Rigoberta Menchu et al. v Ríos Montt et al”., (2013), online: ICD - Ríos Montt - Asser Institute. http://www.internationalcrimesdatabase.org/Case/948/R%C3%ADos-Montt. Accessed 25 January, 2021.

- Thale, Geoff, Jo-Marie Burt & Ana Goerdt. “After the Verdict: What Ríos Montt's Conviction Means for Guatemala”, (9 July 2016), online: WOLA <www.wola.org/analysis/after-the-verdict-what-rios-montts-conviction-means-for-guatemala/>. Accessed 5 February, 2021