BGH Book Club: The Devil in the White City

I've been planning on rolling out the unofficial BGH Book Club for a while, so what better day to kick things off than Halloween.

I like to read books. Most of the time they're not specifically horror, but quite often there's a gothic or macabre undercurrent that should make them potent for discussion if folks are so inclined. So every once in a while, I'll toss out a book title, and then a week or so later (depending on how long it takes me to read the thing), I'll write up a post that can serve as a jumping off point for any discussion in the comments. And if anyone has suggestions, just hollar at me. I've got a healthy pile, but I'm always interested to hear about new stuff.

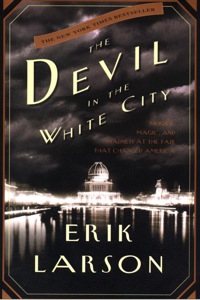

Today, I want to run with the inaugural BGH Book Club selection: Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City. Subtitled "Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America," Larson's book is a non-fiction work that chronicles the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. It takes as its primary characters Daniel Burnham, the fair's creative mastermind, and a man named H. H. Holmes, one of more compelling yet largely unknown (until this book) serial killers in American history. There are essentially two narrative threads that pull us through this work: Burnham's attempt to bring together an almost inconceivably large production, and Holmes's passionate and efficient killing spree that lasted for years. These two narratives never cross explicitly — Burnham was a world renowned architect and would have had no reason to mingle with the likes of a small time wheeler and dealer like Holmes — but they are complementary in many ways, and Larson does an excellent job of weaving these stories together with thematic cohesion and excellent scene setting.

The end of the 19th century was such a strange time, and it's one that doesn't get visited all that often in mainstream cinema or TV: largely because period work is expensive, but I'd argue also because the historical realties of the turn of the century are far more nuanced than most cultural consumers have the patience or knowledge base to revisit. What makes "The Devil in the White City" work is that Larson so deftly fills the reader in on the situation — and continues to do so throughout the work — that it never feels like reading actual history. Even those who come into the book with only a basic understanding of history, like myself, will find themselves totally at home.

The draw here for horror fans will undoubtedly be Holmes' story, and taken in the context of the time, it truly is an incredible one. As painted by Larson, Holmes was essentially a charasmatic monster — a true psychopath, fitting many of the commonly understood markers of the serial killer, but before any of these terms or concepts were truly understood. Holmes was also a man of his era, who took advantage of legal loopholes, shoddy record keeping, and just plain unscrupulous capitalistic behavior to enrich himself. He then turned his considerable wealth and ambition onto the task of creating a "castle" in the midst of Chicago, only blocks from the fair grounds. This building contained all manner of secret passages and lethal traps, all built to Holmes' sick specifications. He put these many deadly elements to good use too, killing sometimes for financial gain, but just as often for pure pleasure.

There's many things that made this book a smash hit, but Larson's frank and often chilling portrayal of Holmes's actions probably ranks at the top of the list. The work is non-fiction, but Larson does his best to juice it up with gory details and even some healthy speculation about Holmes's murders. The fact that the work is so well reported, and so effectively laid out makes it all the more frightening because it's impossible to push this evil out of your mind. Holmes isn't a creaking monster or supernatural ghoul: he's a real dude who got his kicks by cutting up women, and occasionally men and children.

"The Devil in the White City" rises above other serial killer works by elevating the man into a myth, and tying that myth into a larger story about modernization and incredible growth across the United States. Larson positions both Burnham and Holmes as men ahead of their time; as men who were pulling America into the 20th century. And while these two men stand at opposite ends of a grand specturm — one the ultimate creator, the other a destroyer — they describe a path that eventually points the way to the vast changes that awaited in the 20th century.

Next Time at BGH Book Club: The Pale Blue Eye.